Restor8 design Solutions is proud to present our new Digital Gift Card Scheme these Gift Cards are presented in PDF format for speed of delivery. These cards have a detailed classy design and are available in 3 amounts. These are £15, £25 and £50. Gift Cards are a great way to give people that extra special gift and here at Restor8 Design Solutions we embrace this. These cards can be used up to the value on the face of the card for payment or part payment of services at Restor8 Design solutions.

This is what the cards look like:

Friday 1 April 2011

Monday 31 January 2011

Protecting and how to Preserve Old Photographs

But many family historians have been horrified to find a stash of priceless photos stuck together, cracked, bent, faded or mildewed. Here are guidelines for protecting and displaying these historic photographs.

Photos are typically made up of three main layers: the image material, the support to which the image is adhered, and the binder which holds the two together. Any or all of these may become damaged in a variety of ways.

Environmental Factors can Damage Vintage Photos

Heat, humidity, and exposure to light are prime causes of vintage photo deterioration. All three create chemical changes in the compounds that make up the photo. The image can fade, become blotchy or change colors. The support material may separate, curl, or disintegrate. Humidity can encourage mold growth on the photo.Other chemical reactions can cause damage to old photos, especially when stored or displayed with non-acid-free products. Film-based negatives can produce acid gases, and should be stored separately from the photographs.

Use Archival Products for Photo Storage

Safe photo storage includes using archival quality products. Old vinyl sheet protectors release chemicals that can lead to deterioration. “Magnetic” and other self-adhesive photo albums contain materials that can leave damaging residues on vintage photos. Even paper and picture frames can contain high-acid wood pulp.Today’s archival products are created with long-term stability in mind. Archival sheet protectors and other plastic sleeves should be made of uncoated polyester, polypropylene, or polyethylene. Album paper, paper envelopes, and paper photo mounting corners should be lignin-free and 100 percent rag or alpha-cellulose fibers. They should be white or off-white, not dyed.

Frame and Display Old Photos Carefully

Old photographic images vary in stability, according to what process was used to create them. Direct sunlight will damage any photograph, and even unfiltered fluorescent lights can accelerate fading.If antique photos are being framed and displayed, never place them where direct light from a window will touch them, and be careful what other lights are used in the area. Ultraviolet-filtering glass can reduce the effects of light somewhat. Make sure the frame, mat, and mounting material are archival quality. If a frame shop does not have archival products, ask if you can provide your own.

Daguerreotypes, Tintypes and Ambrotypes: Professional Conservator Required

When the original photographic process reproduced the image directly on to metal or glass, as with daguerreotypes, tintypes and ambrotypes, the resulting photo is easily scratched or destroyed. These types of antique photos were enclosed in glass for protection, and then often kept or displayed in a wooden frame.The problem now is that the glass may have cracked, become dirty, or otherwise deteriorated, but removing the glass from the photo can damage the photo irreparably. Any family historian with a daguerreotype, tintype or ambrotype should consult a professional conservator for advice and assistance. A museum with photographic collections can help locate an appropriate professional.

Scan Old Photos for Preservation

While genealogists and history lovers want to preserve their photos, many still want to enjoy them on a daily basis. The best solution for any priceless photo is to keep it in appropriate archival quality storage in a safe place, and to frame and display a reprint instead. This also protects against disasters such as fire or flood.Today’s digital imaging technology is accessible to anyone with a computer. Photos can be scanned and retouched, and then multiple copies made and distributed, all while the original lies safely tucked away.

Recognition and Dating of old types of photograph.

During the early years of photography, there have been basically 3 overall types of photographs (in terms of materials they were printed on): paper and cardboard, metal or glass. The most common are photos on paper, and their main types are the Carte-de-visite, the cabinet card and the photo postcard.

Metal photos were either tin-type or daguerreotype, and photos on glass were likely ambrotypes. Each type of photo has a time-frame and use associated with it. Since the metal/glass photos are relatively rare, this article will focus on the more common paper/cardboard varieties.

Carte-de-Visite

Also referred to simply as cartes. These small photos were glued to a cardboard backing that was about 10cm by 6cm in size. The size was constant because photo albums of the day were made with holes cut in the stiff pages to hold these carte photos. The backing card was usually decorated with the name of the photographer, along with some decorative flourishes. The earliest cartes are from 1859, and had square corners.In order for the photos to slide smoothly into the albums, they started being made with rounded corners around 1872. But the square corners did come back again later in 1900, possibly as the use of albums became less popular. The card backing was quite thin with the earlier photos, and got heavier as the years progressed. Those made after 1880 were very thick and sturdy. Carte-de-visite stopped being produced in the early 1900s.

Cabinet Card

A similar style and design of photo as the above described cartes, but larger. Also mounted on cardboard backing, these photos also showed the name of the photographer on the back, or under the photo on the front. Cabinet cards were about 16 ½ cm x 10 ½ cm in size. Cabinet cards date a little later than the Carte-de-visite, being first introduced around the late 1860s.Most of them are dated from the 1870s though. These photos always had rounded corners until 1900, when both rounded or square cards were produced.Photo Postcard

I'm sure the name explains this one. It became popular to have photos printed directly on cards that could be sent through the mail, as a convenient way to share photos with friends and family. These cards are around 14cm x 9 cm, and have obvious postcard markings on the back. If you're lucky, a used card will have a dated postmark. Photo postcards were being made in the very early 1900s, just as the other styles of photos were losing popularity. They continued in production as late as the 1940s and 1950s.Dating Old Photographs

If you have old photographs with no dates, there are ways to narrow down the time frame of when they were likely taken. Look at the clothes, and the type of photo itself.

In your collection of old photos, do you have some with no dates nor any clear way of telling when the photo was taken? If you know who the person is, then you can narrow down the dates somewhat but who doesn't have a few mystery photos with no notes sitting in their history collections, just crying out for further identification.

If you can pinpoint the date (somewhat) then you may even be able to figure out who the person is by connecting them with the right generation in your family tree. Family resemblance is a very handy tool, but remember that your great-grandmother may have looked an awful lot like your own mother when she was younger. Dates can help eliminate that problem.

Ladies fashions are usually used as a date indicator, since they changed far more frequently than men's fashion. Dress styles, presence or absence of hats and other accessories, hair styles and even poses. Fashion-Era is an excellent website to explore the fashion styles of the past. There are pages for the 1800s but most of the site focuses on the styles of the 1900s. You can also find some great examples and quick things to look for at Family Chronicle.

Another way to tell the age of the photo, is the style and format of the photo itself. Is it printed on a cardboard card with the photographer's name on the back, or is it a thin sheet of metal mounted in a matte frame? Or are your family photos actually printed as postcards, designed for easy mailing? You can narrow down the date window by using the type of photo.

The Brownie camera was invented in 1900 and became wildly popular in the 1950s, allowing anyone to take their own photographs. During this time period, you'll find many more amateur photos which can offer many more clues by letting you see the backgrounds of candid shots. Once cameras were basically available to anyone, you'll find many more family photos since it no longer required an expensive trip to the studio.

Modern-era photos are much easier to identify because we are all still reasonably familiar with the time frame, including fashion and other indicators. That photo of your aunt in the day-glow bell bottoms must certainly date to the 70s.

Wednesday 22 December 2010

How Restor8 Design Solutions is different from other restoration companies.

Most Photo Restoration companies will prefer to restore the photographs from their local areas. Well this is not the case for us at Restor8 Design Solutions we feel the photo's of the world need attention too not just that of the local area or the United Kingdom.

With this in mind we recently restored a photograph that came all the way from Brazil. This photo was in a bad state of repair and not only that it started life as a 1"x1" slide which with the knowledge, skill and specialist software we were able to restore this and resize up to A4.

There was a lot to do on this as it needed to have various things done ranging from brightness and saturation right upto elements being replaced and everything in between. This restoration came under the major restoration category.

With this in mind we recently restored a photograph that came all the way from Brazil. This photo was in a bad state of repair and not only that it started life as a 1"x1" slide which with the knowledge, skill and specialist software we were able to restore this and resize up to A4.

There was a lot to do on this as it needed to have various things done ranging from brightness and saturation right upto elements being replaced and everything in between. This restoration came under the major restoration category.

Tuesday 21 December 2010

Edweard Muybridge - One of the most innovative pioneers of photography

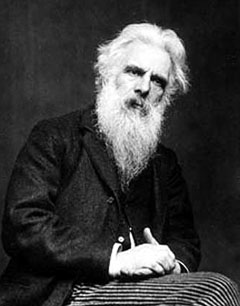

Eadweard Muybridge

One of the most innovative pioneers of photography, Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) is perhaps best known as the man who proved that a horse has all four hooves off the ground at the peak of a gallop. He is also regarded as the inventor of a motion-picture technique, from which twentieth cinematography has developed.

Muybridge was born Edward James Muggeridge on April 9, 1830, in the town of Kingston-on-Thames in Surrey, England. When he was 20 years old, he changed his first name to conform to the Saxon spelling and a possible Spanish lineage; he became "Eadweard." His surname was altered in stages; it went from Muggeridge to Muygridge and finally Muybridge.

Relocated to San Francisco

Despite his affinity for British antiques, styles, and customs, Muybridge saw his future in the United States. After a brief stay in London, he immigrated to the United States in 1851. He found work as a commission merchant, initially for the London Printing and Publishing Company and later for Johnson, Fry and Company (for whom he acted as business agent). He was involved in the importation from England of unbound books, which were then bound, sold, and distributed in America. By all accounts, Muybridge was a good businessman who, in just a few years, had set himself up nicely.

During this time he made the acquaintance of Silas T. Selleck, a daguerreotypist (a photographer who makes a photo on a plate of chemically-treated metal or glass). Selleck, no doubt, opened up the world of the image to Muybridge. In the meantime, gold fever infected Selleck, who headed west. He eventually established a photography studio in San Francisco, and the lure of California became stronger to Muybridge. In 1855, he decided to join his friend.

By the time Muybridge arrived, the first boom of the great California gold rush had subsided and San Francisco itself was in a recession. An astute businessman, Muybridge still managed to thrive. He opened a bookstore downtown through which he sold material supplied to him by the London Printing and Publishing Company. Above the bookstore he opened an office as the commission merchant for the company.

Muybridge's business opened up new avenues to him. He became a board member of San Francisco's Mercantile Library Association, which promoted reading by sponsoring a library and lectures, and San Francisco's intellectuals frequented his business. He also brought his two younger brothers, first George (who died in 1858), then Tom to San Francisco.

By the late 1850s, Muybridge's attention began to turn away from business. Travel in California and new techniques in photography had spurred his interest in landscape photography. Muybridge was not a pioneer in this field. The photographs of Charles L. Weed, Robert Vance, and Carleton Watkins were already for sale in San Francisco. Still Muybridge hoped to photograph California more extensively than they had done. Subsequently, he gave up both his businesses. The bookstore was turned over to a music publisher, while his brother Tom became the San Francisco commission merchant for the London Printing and Publishing Company.

After giving up his businesses, Muybridge set out on an extended trip to Europe. His plan was to travel east via stagecoach, before sailing abroad. Along the way, the stagecoach crashed and Muybridge was injured. He remained unconscious for several days. His vision and senses of taste and smell were affected. Arriving in New York City, he sued the company, and then sought medical treatment in London. He briefly returned to New York to settle his lawsuit, but eventually returned to Kingston-on-Thames to recuperate further.

While in Kingston-on-Thames, Muybridge befriended Arthur Brown, a man who furthered Muybridge's already keen interest in photography. Muybridge at this time also tried his hand at invention and improvement on already existing patents. He himself sought a patent on a washing machine and though it was never granted, Muybridge did receive other patents in the United States and England.

In his book Muybridge: Man in Motion, Robert Bartlett Haas describes this time period (1860-66) as Muybridge's "lost years." In fact, Muybridge was really developing a plan. He devoted more and more time to his craft just as new photographic techniques were being developed. He eventually decided the United States, as both subject and market, offered the best opportunity for a budding photographer.

Full-Time Photographer

Muybridge made his way back to San Francisco, now much changed and even more to his liking. If he had had any second thoughts about returning to his old business ventures, they quickly vanished. He was now a professional photographer, and briefly shared a studio with his old friend, Selleck.

He first concentrated on scenes of San Francisco, a city of approximately 200,000 people in 1870. He began taking cityscape photographs of San Francisco in 1867 and would continue to do so until 1881. Many of Muybridge's early photos were of San Francisco Bay from various vantage points, but he also took numerous photographs of city life, notably the architecture. Among his better known photographs at this time were "Pacific Bank, Sansome Street," "Merchant's Exchange, California Street," "Montgomery Block," "Montgomery Street, north from California," "Maguire's Opera House," "Trinity Church and Jewish Synagogue," "The Cliff House," "Russian Hill from Telegraph Hill," and " Montgomery and Market Street, Fourth of July." These photos reflect the growing city, as it emerged to become the most important cities in California.

In 1872 and 1873, Muybridge began to photograph what has become his signature series, a galloping horse. Legend has it that a $25,000 wager between former California Governor Leland Stanford and a rival was involved, but Muybridge's own account makes no mention of the bet. It is believed that Stanford hoped to use the information to breed and train better race horses, while Muybridge was interested was in animal locomotion. But as the Masters of Photography website noted that "The experiments were interrupted when Muybridge was tried in 1874 for murdering his wife's lover.

Marriage and Murder

In 1872, Muybridge married Flora Stone, 22 years his junior, whom he had met when she had worked as a photographic re-toucher at another studio. Their brief marriage would culminate in one of the city's biggest scandals of the decade. Into their circle came Harry Larkyns, a former major in the British army who in 1873, had become theater critic for the San Francisco Post. Larkyns possessed all of the outgoing qualities Muybridge lacked, and it wasn't long before he had thoroughly charmed Flora.

While Muybridge also returned to his original photographic purpose, taking photographs in America's Northwest, Flora and Larkyns became lovers. Muybridge ideas expanded, and he photographed members of the Modoc tribe, Vancouver Island, and Alaska, as well as produced a series of photographs that followed the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads from San Francisco to Omaha, Nebraska. Meanwhile, back in san Francisco, Flora became pregnant, and Larkyns was rumored to be the true father of her child.

When the rumors as well as the with near undeniable evidence came back to Muybridge, he set out to kill Larkyns who had already fled San Francisco. In October of 1874, Muybridge shot and killed Larkyns. He was indicted for premeditated murder, and his trial was held in early 1875. He was found not guilty after a short trial.

Muybridge decided he needed a change of scenery and decided to take his camera to Central America. He spent 1875-76 primarily in Guatemala and Panama, concentrating his camera lens on cities such as Colon, Panama City, and Guatemala City, as well as the surrounding countryside, which yielded completely fresh subject matter.

While he was in Central America, Flora died and her child, Floredo, was placed in an orphanage. Upon his return to California, Muybridge learned of her death. Though he was convinced he was not the boy's father, he did regularly visit Floredo at the orphanage. In 1877, Muybridge resumed his work with Stanford.

Muybridge photographed Stanford's racehorse, named Occident. The purpose of the photos was to determine whether all four of a horse's hooves are off the ground at some point in a gallop. Muybridge had already developed automatic shutters, which he then set up in a dozen cameras along a Sacramento racecourse. (The Washington Post noted that "Muybridge's studies are so cleanly, almost starkly, done that it's easy to forget the endless drudgery involved.) As Occident galloped past, the horse tripped wires that were connected to the shutters. The photo series of Occident proved that all four of a horse's hooves are off the ground at some point.

In 1877, Muybridge photographed another of his masterpieces. He set up his camera on the San Francisco's famed Nob Hill, where he had already been commissioned to photograph the mansions, and took a panorama of the city using eight by ten-inch plates. The result was a magnificent view of the city on 11 panels that stretched to seven and a half feet in length. Muybridge published this as "Panorama of San Francisco from California Street Hill."

Early Motion Pictures

Muybridge was not only fascinated by animals in motion, he was intrigued with devising a method of having photographs depict motion. The Masters of Photography website described this as "stop-action series photography."

He had already experimented with various automatic shutters to quickly capture movement when in 1879, he developed what he initially called the zoogyroscope, which later became known as the zoopraxiscope. As defined by the Masters of Photography website, a zoopraxiscope was a "primitive motion-picture machine which recreated movement by displaying individual photographs in rapid succession."

Muybridge used glass disks with sequential photos on each disk of a horse in motion as the "slides" for his projector. This pioneering method predated Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope and even influenced it. Many now believe that Edison's work was a refinement of Muybridge's, albeit a vastly improved refinement.

Muybridge spent much of his later career at the University of Pennsylvania. He took photographs between 1884 and 1887, demonstrating animal and human motion and movement. The result was Animal Locomotion,published in 1887. The Masters of Photography website described it as "the most significant work was the human figure."

The website added that it was "a visual dictionary of human and animal forms in action." The 11-volume series showed male and female models, both nude and clothed, photographed in all kinds of activities—walking, running, playing games, climbing stairs, etc. Muybridge even photographed a girl throwing a bucket of water over another girl, and a mother spanking a child.

By now Muybridge was well known on the lecture circuit, not only in California, but on the East Coast and in Europe. He continued his studies of animal motion, and displayed the zoopraxiscope at the Columbian Exposition of 1893.

In his last years, he returned to Kingston-on-Thames where he died on May 8, 1904. The Washington Post,concluded that Muybridge "showed the world how people and animals actually move and permanently altered our perception of time and space."

An Introduction into Photography and Restoration

Back to main

Photography is the ability of the medium to render seemingly infinite detail, to record more than the photographer saw at the time of exposure, and to multiply these images in almost limitless number made available to the public. Yet, we must not forget the aesthetic and artistic value of photography. It is not merely a mechanically reproducible medium with many functional purposes and objectives, but it is also an art form created by a more modern and methodical type of artist (the photographer) who wants to depict the world in a different way than the painter or the sculptor. The artist gives us, in a sense, a kind of coated reality of his construction that can only be transmitted through a photograph.

Our photographs mean a lot to us, and we value them. We put them into photo albums, place them in picture frames, display them in our homes and offices and carry them with us in our purses and wallet. We even put our photographs on our t-shirt and bags. That is how important photographs in the lives of most people.

Traditional Photo Restoration is performed by skilled traditional photo specialist in their darkroom. Their tools include artist brushes, retouching dyes, fixers, toners and other chemicals, mixing pallets, baths, enlargers, film tanks and other darkroom equipment. They do retouching by hand with artist brushes and dyes, and they use enlargers for adding and subtracting exposure to prints (i.e., dodging and burning), and filters for adjusting contrast.

On the other hand, Digital Photo Restoration is performed by graphic artist where they use tools such as scanners, computers with high-end photo editing software (Adobe Photoshop, Corel Painter, Paint Shop Pro, and Gimp), high resolution monitors, and photo quality printers, paper and inks. They restore photos with a mouse or table pen, and save their work as electronic files that can be printed, emailed, or stored on removable media such as flash drives and etc.

The rapid advancement of technology will always find methods that are more convenient and fast over the years, traditional photo retouching is replaced by digital photo restoration due to the latter's long hours of work and complexity.

The Value of Photographs

Photograph, technically, is an image created by light falling on a light-sensitive surface, usually a photographic film or an electronic imager. Photos are snapshots in time that record the important people, places, and things in our lives. They also capture important events in our lives, and serve to augment our memories. Most photographs are created using a camera which uses a lens to focus the scene's visible wavelengths of light into a reproduction of what the human eye would see. The process of creating photographs is called photography.Photography is the ability of the medium to render seemingly infinite detail, to record more than the photographer saw at the time of exposure, and to multiply these images in almost limitless number made available to the public. Yet, we must not forget the aesthetic and artistic value of photography. It is not merely a mechanically reproducible medium with many functional purposes and objectives, but it is also an art form created by a more modern and methodical type of artist (the photographer) who wants to depict the world in a different way than the painter or the sculptor. The artist gives us, in a sense, a kind of coated reality of his construction that can only be transmitted through a photograph.

Our photographs mean a lot to us, and we value them. We put them into photo albums, place them in picture frames, display them in our homes and offices and carry them with us in our purses and wallet. We even put our photographs on our t-shirt and bags. That is how important photographs in the lives of most people.

The Difference between Traditional and Digital Photo Restoration Methods

Photos means a lot to us that 's why we put them in a place that can't be easily damage but no matter how we keep our photos safe, the deterioration of something tangible is inevitable. And that is how Photo Restoration came upon. Photo restoration is performed by a skilled restorer or graphic artist. They can take those damaged and weather-worn photographs and restore them either close to , or exactly how they were when they were new; and can even improve the photographs.Traditional Photo Restoration is performed by skilled traditional photo specialist in their darkroom. Their tools include artist brushes, retouching dyes, fixers, toners and other chemicals, mixing pallets, baths, enlargers, film tanks and other darkroom equipment. They do retouching by hand with artist brushes and dyes, and they use enlargers for adding and subtracting exposure to prints (i.e., dodging and burning), and filters for adjusting contrast.

On the other hand, Digital Photo Restoration is performed by graphic artist where they use tools such as scanners, computers with high-end photo editing software (Adobe Photoshop, Corel Painter, Paint Shop Pro, and Gimp), high resolution monitors, and photo quality printers, paper and inks. They restore photos with a mouse or table pen, and save their work as electronic files that can be printed, emailed, or stored on removable media such as flash drives and etc.

The rapid advancement of technology will always find methods that are more convenient and fast over the years, traditional photo retouching is replaced by digital photo restoration due to the latter's long hours of work and complexity.

Thanks to lazymask for this article.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)